Climate justice in trade

Environment, rights and the palm oil dispute between Indonesia and the European Union

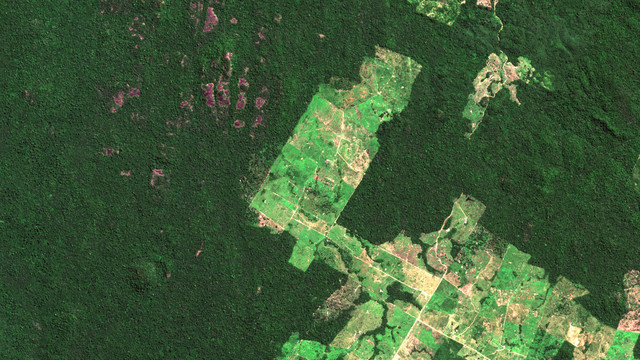

Palm oil plantations in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia (Photo: Victor Barro, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Ferdi Kurnianto, Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago AMAN), Central Kalimantan, IndonesiaWhile Europeans use palm oil products to fuel their cars, many in Indonesia are deprived of their rights, suffer and even die from the processes of producing palm oil

Ferdi Kurnianto advocates for the rights of Indigenous Peoples affected by oil palm plantations in Indonesia’s Central Kalimantan province, acting as the local coordinator for the Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago (AMAN). In this sentence, he captures some of the complexities of climate justice in our interconnected world.

With pressures on ecosystems drawing closer to a tipping point, governments are taking steps to promote ‘greener’ economies. But in their efforts to reduce carbon emissions, high-consumption states have often outsourced harmful activities without really questioning unsustainable consumption, helped by trade arrangements that connect consumers with producers in far-away places.

To lessen its dependence on fossil fuels for cars and trucks, the European Union (EU) promoted the use of ‘biofuels’, such as biodiesel from palm oil imports – and this contributed to the spread of the plantations in Indonesia.

Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. The province hosts extensive oil palm plantations (Image: IIED)

A joint initiative between IIED and the Indonesia Legal Aid Foundation (YLBHI) provided opportunities to interrogate trade rules from a climate justice perspective, honing in on palm oil trading between Indonesia and Europe.

The findings connect the concerns and aspirations of communities affected by oil palm cultivation in Central Kalimantan to European policies and international trade talks. They also highlight ways to make trade arrangements more responsive to the people who most bear their impacts.

Trading virtual farmland

When the EU introduced the Renewable Energy Directive (RED) in 2009, the legislation was heralded by many as an ambitious step to shift energy consumption away from harmful fossil fuels. The RED set new targets for using fuels made from plants to power trucks and cars.

Within ten years, more than half of the EU’s palm oil imports were for biodiesel, with heating and electricity on top of that; taking palm oil imports the EU burned for energy to a total of 65%.

Palm oil exports from Indonesia to the EU increased from 750,000 tonnes in 2000 to nearly 3.4 million in 2020, with a sharp upturn as the 2009 directive was being discussed and with subsequent peaks of more than 3.7 million tonnes.

Source: Data Eurostat

Coupled with demand in other markets, such as India, this export boom fuelled the rapid growth of Indonesia’s palm oil industry, which was first established during colonialism and expanded after independence. The non-governmental organisation FERN estimated that Indonesia’s oil palm estate expanded from 9.6 million hectares in 2012 to some 14 million in 2019.

This contributed to making the EU a major net importer of virtual farmland – a phrase denoting that Europe’s consumption depends heavily on land cultivation overseas. According to data from 2017, a growing share of the EU’s ‘virtual land’ footprint was in the form of oil palm plantations, particularly in Southeast Asia.

A climate justice issue

In Indonesia, millions of people work in the palm oil sector, including as plantation workers and smallholders integrated into corporate supply chains. The government has championed the industry’s expansion as part of strategies to promote economic growth.

But oil palm has also engendered profound transformations in Indonesia’s countryside. As research by scholars Tania Li and Pujo Semedi shows, the plantation model enables a corporation to take over the management of space, time, nature and people in often vast territories.

The spread of oil palm has dispossessed Indigenous landholders, triggered thousands of land disputes, raised concerns about labour conditions, and driven deforestation, pollution and the destruction of natural habitats.

The men and women participating in the action research facilitated by YLBHI and IIED highlighted the far-reaching impacts of these pressures on the living space of indigenous communities in Central Kalimantan.

Muhammad Habibi, an activist at Save Our Borneo, and Ferdi Kurnianto emphasised that the environmental damage caused by oil palm is closely related to social problems – including land dispossession, reduced access to cultural sites and fishing or hunting grounds, and an erosion of traditional ways of life.

In these ways, EU renewable energy policies transferred the social and environmental costs of Europe’s climate transition to people in Indonesia. Advocates in Central Kalimantan have mobilised to protect their land rights, document and revive their traditions, investigate company permits and support land rights defenders from intimidation.

Ironically, industrial-scale palm oil production in Indonesia is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions, potentially offsetting the emission reductions Europe hopes to achieve through its renewable energy transition.

As forest burning is a common method to clear land, land use change lies at the heart of this problem, especially on land with high carbon stock such as forests, wetlands and peatlands.

This includes the clearing of land to create oil palm plantations. It also includes so-called ‘indirect land use change’ (ILUC) – a sanitised description of the process whereby landholders dispossessed by oil palm clear forests elsewhere to grow their food.

Protest against oil palm developments in Central Kalimantan. The big banner reads: “Customary forest is not for clearing" (Photo: AP AMAN Kalteng)

Shifting public policies

Indonesian activists know the government has played a key role in promoting the plantations and they are familiar with the close relationships between public authorities and oligarchs with vested interests in the industry. But they also see Europe’s role in driving demand for palm oil.

Activists have been advocating to change Indonesia’s national policies and laws, including to strengthen recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ rights. They established national coalitions, conducted public campaigns and engaged with the media.

They have also established alliances with environmental activists in Europe. This advocacy has helped to achieve policy changes, including a 2015 amendment to the EU RED and a full ‘recasting’ of the directive in 2018.

The 2018 Directive – RED II – requires EU members to source at least 14% of energy for transport from renewables by 2030. Importantly, the reformed RED aims to address the environmental impacts of renewables more fully: the contribution of high ILUC risk biofuels towards the renewable transport target is capped and will be phased out and excluded from financial support. Products that are specifically certified as low ILUC risk are exempt.

A subsequent EU implementing regulation established the methodology for assessing ILUC risk. Based on an empirical analysis of the spread of oil palm cultivation, the EU identified palm oil as a high ILUC risk biofuel – the only feedstock to feature in this category.

A road was built by a palm oil company operating in Central Kalimantan, replacing natural forest. As the forest disappears, so does the village’s hunting culture (Photo: AP AMAN Kalteng)

RED II is part of wider EU efforts to address the adverse impacts of Europe’s demand for commodities. For example, the EU has adopted a Deforestation Regulation governing crops that are considered major drivers of global deforestation, including palm oil. This regulation will require companies to ensure that the produce they sell in the EU is not linked to deforestation.

From environmental action to trade disputes

The Indonesian government, meanwhile, saw RED II and its implementing measures as a protectionist scheme harming its exporters in breach of the rules of the World Trade Organization (WTO), which require states not to discriminate against imports from a trading partner.

While the EU measures did not ban palm oil, they sharply reduced the market and financial support for exporting uncertified palm oil to the EU. And while RED II is formulated in neutral terms, its implementing instruments single out palm oil – a commodity virtually not produced in the EU.

The Indonesian government submitted a complaint to the WTO and, in 2020, the WTO set up a panel to decide on the dispute. The panel will determine whether the EU measures discriminate against Indonesia’s products and, if so, whether the measures are justified under the WTO’s environmental exceptions.

Trade lawyers have already offered technical commentaries on which legal arguments are likely to gain more traction. But from a policy standpoint, the story of palm oil highlights questions about whether international trade rules adequately address climate justice concerns.

The rise of ‘sustainable development’ in trade agreements

Social and environmental issues are increasingly prominent in trade treaties. In its preamble, the 1994 Agreement Establishing the WTO refers to the ‘objective of sustainable development’. And in a 1998 ruling, the WTO Appellate Body held that this objective should ‘add colour, texture and shading’ to the interpretation of all WTO rules.

WTO rules also enable states to take measures ‘necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health’ or ‘relating to the conservation of exhaustible natural resources’ if the measures comply with certain requirements.

In Central Kalimantan, a man uses nets to fish in the river. Villagers find that pollution caused by large-scale oil palm cultivation has made it more difficult for them to catch fish (Photo: AP AMAN Kalteng)

Many regional and bilateral trade agreements contain ‘sustainable development’ provisions that go beyond WTO rules. The EU has been a leader in this process, which trade law scholar Clair Gammage has termed a ‘shifting paradigm’: over the past few years, the EU has consistently negotiated chapters on sustainability in its trade treaties.

In the trade agreement between the EU and Viet Nam, for example, the two sides reaffirm their obligations under the 2015 Paris Agreement and other multilateral environmental agreements, and make commitments on ratifying and complying with key international instruments on labour rights.

These are significant advances, but much remains to be done: for one thing, while labour and the environment are important issues, sustainable development is a more encompassing concept. Disputes around Indonesia’s palm oil industry highlight concerns not only about climate and nature but also about land and Indigenous Peoples’ rights.

In the eyes of communities at the receiving end of oil palm operations, environmental harm is closely connected to land dispossession and the destruction of traditional cultures and ways of life. Technocratic discussions about land use change do not address the real-life impacts of distributive changes in land rights and territorial control.

Trade arrangements to the test

The WTO palm oil dispute offers a test case on how multilateral trade institutions frame and settle disputes involving complex social, environmental and economic dimensions.

A stalemate affecting dispute settlement institutions has made the implementation of WTO rulings more uncertain. But the decision will send an important signal on the extent to which the WTO system can ensure that sustainability measures such as RED II are even-handed, while also not getting in the way of efforts to make trade more sustainable.

Meanwhile, the EU and Indonesia have been negotiating a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), which would cover trade in goods, as well as services, investment, intellectual property rights and competition. Launched in 2016, the negotiations have been slow, partly due to the palm oil dispute.

In line with earlier EU agreements, the publicly available version of CEPA’s draft sustainable development chapter has a strong focus on labour and the environment. Integrating rigorous requirements on land and Indigenous Peoples’ rights could reinforce the arguments of advocates working to strengthen those rights in the face of oil palm expansion and to change national policy in Indonesia.

Designing new treaty clauses on Indigenous Peoples’ rights could build on emerging practice, such as the process through which the government of New Zealand engaged with the Māori in its trade treaty negotiations. New treaty clauses on land and Indigenous Peoples’ rights could also cross-reference existing international instruments: the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas.

Recently planted palm oil plantation on rainforest peatland in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia (Photo: Glenn Hurowitz, via Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

Sustainability for whom?

However, even these novel clauses would fall short of confronting the more fundamental questions raised by trade agreements that promote large-scale monoculture at the expense of nature and local farming systems. Palm oil highlights how consumption in Europe drives social and environmental problems in Indonesia.

The EU Deforestation Regulation reflects a laudable effort to address the impacts associated with the large-scale consumption of agricultural commodities. But the regulation also raises questions about a rich economy unilaterally imposing its rules on what counts as sustainable. This sparked major concerns in producer countries, with the Indonesian government accusing the EU of ‘regulatory imperialism’.

According to Giorgio Budi Indrarto, deputy director at Indonesian non-profit Madani, the regulation could still be an opportunity to more effectively implement Indonesia’s laws, rather than a new source of trade dispute, but only if the EU takes a more collaborative approach, including with civil society and small-scale oil palm growers in Indonesia.

Sustainability laws such as RED II and the Deforestation Regulation highlight the extraterritorial reverberations that domestic policies can have, and the value of civil society scrutinising and advocating in relation not just to international treaties and negotiations but also to the transnational arrangements that govern global trade.

Ultimately though, taking climate justice seriously will require a rethink of consumption patterns in richer countries, reducing our dependence on cars and promoting more sustainable, equitable societies. Activists in Central Kalimantan expressed deep scepticism towards top-down sustainability agendas that do not tackle the fundamentals and that, in practice, enable industrial-scale forest conversions.

As Ferdi Kurnianto noted, for many village communities, sustainability is not just about how oil palm is cultivated; it “relates to their living space… their food… and their generations”. It is about whose voices count, whose vision of ‘development’ is prioritised and what types of trade arrangements might help make that vision a reality.

Additional resources

- Read more about work on palm oil trade between Indonesia and Europe: promoting corporate accountability

- Watch a video interview with Muhammad Habibi

- Watch a video interview with Ferdi Kurnianto

- Read a briefing on enhancing coherence in Indonesia’s climate and investment governance, by Pratiwi Febry, Abdul Malik Akdom and Amaelle Seigneret | Dalam bahasa Indonesia

- Read a blog on how nickel mining expansion is impacting agrarian economies in Indonesia, by Mutmainnah Adenan and Imran Tumora | Dalam bahasa Indonesia