What does low-carbon resilience look like in Latin America?

When it comes to low-carbon resilient development, Latin American countries face a unique set of challenges around economic growth and deforestation. But by adopting climate change polices and strategies, and incorporating low-carbon resilience into national plans, these countries are forging the way. Not only are they addressing national and international concerns, some are finding that there are many co-benefits to low-carbon resilience as well.

Flooded sugar cane fields near Colombia's third largest city, Cali, during an intense rainy season. Severe flooding left 2.2 million people homeless in the country in 2010. Photo: Copyright Neil Palmer (CIAT)

Climate change has a high impact on the national economies of Latin America. These impacts include the rising frequency and magnitude of hazards, such as hurricanes and floods, which have increased significantly during the past decade. In Colombia in 2010, for example, 2.2 million people were displaced and made homeless by severe floods.

The Latin American region comprises a variety of low- and middle-income countries with diverse ecosystems, natural resources and complex socio-economic systems. A couple — Brazil and Mexico — are two of the six emerging economies on the world stage. But in most of Latin America a high proportion of the population still live in poverty despite local and regional economies having been strengthened. This means it is the vulnerable and the poor who will be most affected by climate change.

This vulnerability and the need for political action has been recognised: Latin American countries have joined the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and are beginning to prepare mitigation and adaptation actions. Some have included these efforts into their national development planning — 12 out of 17 countries in the region have included climate change in their national development plans. The countries furthest forward in terms of climate change strategies and plans in the region are Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico and Peru.

While Latin American countries are vulnerable to climate change, many also have a unique position in addressing the issue. That’s because they hold some of the world’s largest forests, which are huge sinks for absorbing greenhouse gas emissions. This means low-carbon resilience may look very different in Brazil than it does in Rwanda, for example.

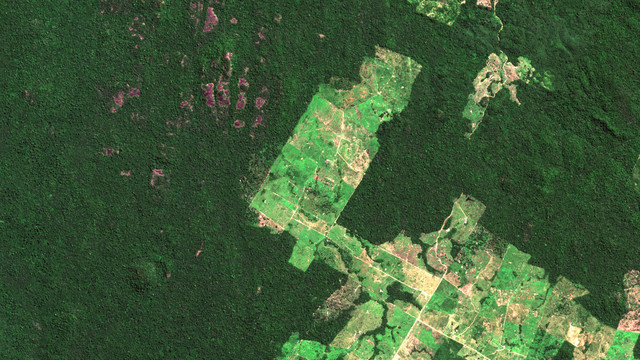

Land use change, in particular deforestation, is often the main source of national greenhouse gas emissions in Latin American countries. This makes it a global issue, so the international community is supporting countries in the region to reduce deforestation through UNFCCC programmes, such as Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) and Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF), which are being utilised across the continent.

Protecting the forest

Brazil is one country that is making national commitments to prevent deforestation. It is strongly committed to voluntary action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions — 75 per cent of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions result from deforestation.

Brazil launched its National Plan on Climate Change in 2008, which calls for a 70 percent reduction in deforestation by 2017. It went on to adopt a National Climate Change Policy in 2009 that lays out voluntary reduction targets for greenhouse gas emissions.

Many studies on options for low-carbon development have also been carried out, including a low-carbon country case study, a policy proposal for a low-carbon economy and a report by the Carbon Trust looking at Brazil’s potential for a low-carbon economy.

The Forest Investment Programme (FIP) is supporting Brazil to achieve these objectives. The FIP is a Climate Investment Fund, which provides investment to reduce deforestation and forest degradation and promote sustainable forest management, so that emissions can be cut and forest carbon stocks enhanced.

As well as deforestation, Brazil is also addressing energy issues as part of its commitment to low-carbon resilience. The National Plan on Climate Change outlines that Brazil should continue to generate more than 80 per cent of its power from renewable energy sources through to 2030, and establishes a quota of renewable energy and biofuels usage.

There has been some criticism [PDF] of Brazil’s targets for cutting carbon emissions, but the National Plan does indicate a strong commitment to a low-carbon future, where Latin America is leading the way.

Other countries in the region, such as Colombia, with different priorities and needs than Brazil, are also developing low-carbon development strategies. These are designed to create ‘win-win’ scenarios, which support both economic development and greenhouse gas mitigation. But in each case, the need for ambition must be tempered with the need to develop — and secure — resilience.

Adopting policies and legislation on low-carbon resilience often depends on using co-benefits to build political and popular support — that is, using measures that bring other benefits as well as reducing carbon emissions. Many countries that focus on energy policies as part of a low-carbon strategy use the co-benefits of energy efficiency, cost savings and improving access to energy. Protecting natural forests in Brazil, for example, has many other co-benefits such as water management, managing soil erosion, protecting livelihoods and storm protection.

Indeed, low-carbon resilience means different things in different countries. In Latin America, many countries are moving ahead on climate change policies and strategies that address national issues and concerns, such as deforestation, as well as international concerns about greenhouse gas emissions. Forestry seems to be one sector where a low-carbon strategy may chime with local needs and national priorities. But co-benefits do need to be further explored to ensure that local, national and international objectives are mutually supportive and deliver the benefits they promise.

Natalia Acero is an intern with the Climate Change Group and a Masters student at Kings College. She has constructed a database of low-carbon and resilient strategies in Latin America. If you wish to find out more, please get in touch by leaving a comment below.