Loss and damage does not happen in a vacuum – it relates to power and politics

Anna Carthy discusses the importance of understanding the history, politics and power dynamics that create vulnerability to loss and damage. Loss and damage is linked to colonial histories and to intersectional marginalisation, and it can be caused by both climate impacts and by climate action.

‘Loss and damage’ refers to the adverse impacts of climate change that have not, cannot, or will not be avoided.

Climate change has already caused widespread losses and damages. These include loss of life from storms, floods and landslides in Rwanda; loss of land and culture from sea-level rise in the Solomon Islands; or loss of Indigenous knowledge from climate-related displacement in the Lake Chad Basin.

As climate-related hazards become more severe and frequent, we are seeing escalating losses and damages concentrated in the global South. This urgent issue of climate justice requires radical action, both now and in the long term.

The reason certain people or groups are vulnerable to experiencing loss and damage is based on power imbalances and marginalisation. Vulnerability is shaped by macro-power relations (or global geopolitics) and micro-power relations (based on intersectional inequalities and marginalisation).

Climate change is linked to colonialism

Some populations have already experienced losses and damages. Loss and damage from climate change builds on a history of loss and damage already inflicted on many global South contexts through processes of colonisation, resource extraction and exploitation, imperialism, maldevelopment and maladaptation projects imposed by external powers.

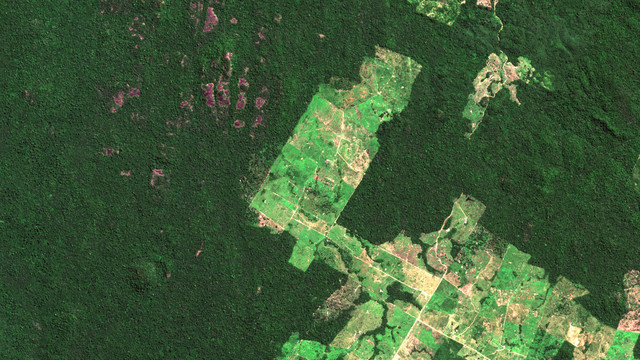

The climate crisis has fundamentally been shaped by racism and colonialism. The historical and political context of how global North nations violently drove the overexploitation of natural resources and benefitted from industrialisation and why formerly colonised countries are most vulnerable to climate change is often overlooked.

This demonstrates a major injustice:

- Colonised territories were (and continue to be) exploited by global North nations for resources to fuel industrialisation...

- which then contributed to increasing greenhouse gas emissions and caused climate change impacts...

- which then hit the formerly colonised territories first and worst.

- The vulnerability of those territories to loss and damage had been heightened by this process, as their ability to cope and adapt was devastated by the colonial era’s destruction and further imperialism and neo-colonialism.

Colonial legacies continue

This historical context formed the political power structures that endure today. Today’s neoliberal capitalism is shaped by continuities from the colonial era.

Certain regions and populations are home to a concentration of power and capital, while others are marginalised: exploited for resources and labour, denied access to capital, forced to face climate impacts, and refused refuge and safe passage when needed.

These regions and their people should not be labelled as simply ‘vulnerable’; they face active and systematic marginalisation by those who currently hold power (and demonstrate agency and resistance in different forms).

Colonial thinking also dominates the international climate policy arena and shapes so-called ‘international development’.

International climate action remains woefully insufficient, and adaptation finance vastly inadequate, meaning international action has neither averted nor minimised loss and damage. This inaction sentences global South countries to compounding and escalating losses and damages, with no finance to address them.

This reproduces the phenomenon of 'sacrifice zones', or as Farhana Sultana says: “Some lives and ecosystems are rendered disposable and sacrificial”.

Development logics and the development industry perpetuate colonial power dynamics. Development, humanitarian and climate finance are mobilised in top-down, paternalistic, neo-colonial ways. Donor-driven interventions don’t give funding, agency or power to the marginalised people whom the finance ostensibly aims to support. These top-down development policies and adaptation interventions reproduce and reinforce existing vulnerabilities.

Climate action can create further loss and damage

Not only does insufficient climate action create loss and damage, some types of climate action – when implemented in the problematic ways described above – can also make people worse off and create loss and damage.

With mitigation, for example, carbon offset projects imposed by global North countries have a history of human rights abuses and have been called “new carbon colonialism”.

On adaptation, there is lots of evidence that top-down adaptation interventions make people worse-off, reinforcing, redistributing or creating sources of vulnerability. This is called maladaptation – explained by Lisa Schipper as “when climate change adaptation actions backfire and have the opposite of the intended effect – increasing vulnerability rather than decreasing it”.

Understanding intersectional vulnerability to prevent maladaptation

Maladaptation can be driven by a shallow understanding of the vulnerability context and a lack of participation by marginalised groups in project design and implementation.

It is critical to understand the context-specific and intersectional vulnerabilities and marginalisation that people face, as well as the history, politics and power dynamics that underlie this marginalisation, before beginning any climate action.

Intersectionality relates to unequal power relations between groups (based on gender, race, disability and more), that create privilege and security for some while creating vulnerability and marginalisation for others.

Marginalised groups face disproportionate vulnerabilities to loss and damage. For example, in Tikapur, Nepal, people from certain ethnic or caste groups (Magar, Chaudhary and Dalit communities) are most affected by loss and damage from floods (PDF). In Urir Char, Bangladesh, people with disabilities and older people are disproportionately affected by loss and damage during cyclones.

Action on loss and damage must learn from this experience

Adaptation research and practice is producing more and more evidence to show that adaptation which does not focus on addressing vulnerability creates maladaptation. Any actors that want to work on loss and damage – at local, national and international levels – need to learn from the failings of adaptation and avoid reproducing the same issues and posing added risks.

Loss and damage action must, therefore, explicitly target and support the marginalised groups that disproportionately experience losses and damages and must address their vulnerability.

Action must be based on a strong contextual understanding of marginalisation so that it does not make matters worse.

Actors who wish to work on loss and damage must hand power over to those who have a deep understanding of their context, in other words, the marginalised people with lived experience of their own marginalisation, resistance and needs.