What does the Biden win mean for climate action?

On climate finance, faster emissions cuts and setting the climate action traffic signal for business from red to green, a Biden administration could produce big shifts.

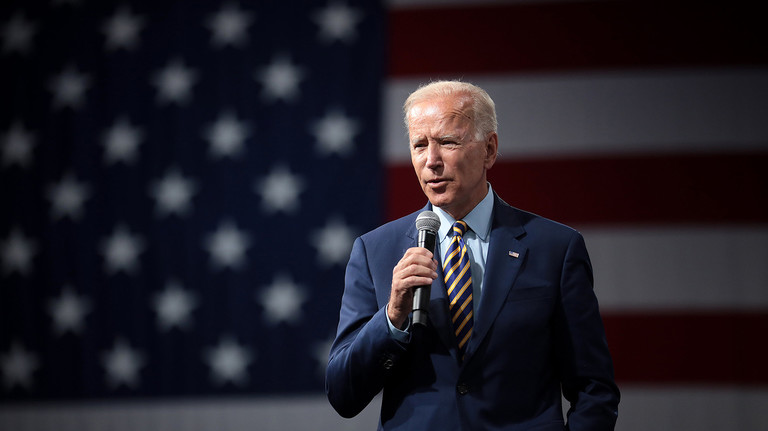

The forthcoming Joe Biden US presidency has already committed to greater climate action and leadership than shown over the last four years (Photo: Gage Skidmore, via Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

There are many reasons to welcome the end of the Trump presidency. Where multilateral processes are concerned, none is more important than President-elect Biden’s pledge to re-enter the Paris Agreement on his first day in office, rejoining global efforts to tackle the climate crisis.

Over the last year, the tectonic plates of the global politics of climate action have started to shift. Progressive countries have continued to plan for change, including those comprising the Least Developed Countries Group and small island states. The European Green Deal (PDF), announced in December 2019, showed how a major economic powerhouse – the European Union (EU) – was gearing up for major investments in inclusive climate action.

When President Xi Jinping announced to the UN General Assembly in September that China was adopting a goal of ‘carbon neutrality’ by 2060, it took the world by surprise. China’s move may have reflected active diplomatic outreach by the EU, particularly Germany, but it likely also reflected a judgement call that a Biden presidency was likely and would be a tipping point in greening the global economy.

We don’t know yet if the Democrats will win control of the Senate. But even without that, the new administration can make a huge difference by acknowledging the scale of the crisis, which Biden’s clean energy and climate plans clearly do, and by re-committing to achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

In addition, he has pledged to hold a global summit to promote climate ambition early in his presidency. There are also commitments to sign a wide range of immediate executive actions on domestic climate and environmental legislation, including strengthening vehicle emissions standards, enacting new efficiency standards and reinstating protections for national parks.

In the realm of climate finance for developing countries, Biden has pledged to reinstate the US funding for the Green Climate Fund, which the Trump administration cut, and can also direct a revamped USAID strongly towards climate action and climate justice.

It is crucial it mobilises US private finance for mitigation, while focusing public climate finance on building least developed countries and other vulnerable nations and communities’ ability to develop and thrive in the face of climate impacts.

Another important area where the Biden administration can unlock finance for lower and middle-income countries is as part of post-COVID-19 economic recovery packages.

Climate change could render the Marshall Islands uninhabitable (Photo: Asian Development Bank, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

By authorising the International Monetary Fund to issue Special Drawing Rights, a Biden administration could unlock up to US$650 billion globally for green and inclusive recovery in developing countries, which have the greatest need and least capacity to borrow independently. The Biden commitment to provide ‘green debt relief’ can open the way for IIED’s proposal of debt for climate and nature swaps.

If the Democrats win the two Senate seats in the January run-off in Georgia, the chances of the Biden administration taking forward its ambitious climate and clean energy legislative agenda become much higher. The $1.6 trillion of investment outlined in these plans could drive domestic change and stimulate a global race in developing the technology needed for a zero-carbon economy.

Going from red to green

At the Paris climate conference in 2015, one phrase was in the air more than any other – that the Paris Agreement would act as a ‘signal to the markets’ of imminent, deep, fundamental structural change in systems of production and consumption to tackle the climate crisis.

Tragically, Donald Trump’s 2016 election set the signal from green to red. Many investors and companies stopped worrying about stranded assets and set about maximising profits, regardless of the impact on the climate. Now, the signal is green again, but we have lost valuable time making it harder to keep global temperature rise below 1.5℃.

The Biden plans, in spirit if not in name, can build on the Green New Deal (PDF) proposal, on its emphasis on both social and environmental justice. Hopefully, the momentum for inclusive climate action will now get stronger, both in the US and globally over the next four years.

This blog was originally published on the Thomson Reuters Foundation News website