What do street food, charcoal, gold, mobile phones and milk have in common?

The short answer is informality: they are all often produced, processed or sold by people who operate outside formal rules and regulations. But these small markets add up to big business.

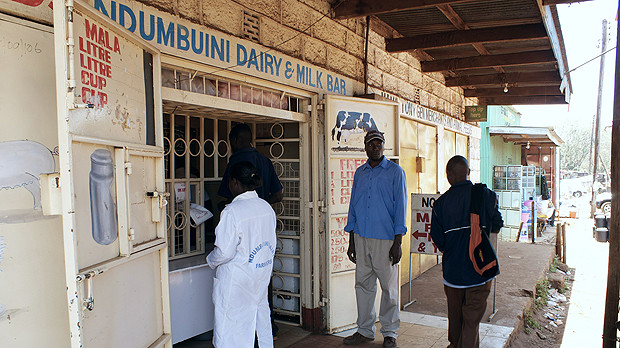

Customers at a milk bar in Ndumbuini in Kabete, Nairobi. Research in Kenya has found that milk sold in this way had similar bacterial levels to those sold in formal markets (Photo: ILRI/Paul Karaimu)

In Colombia, a country that's a big gold producer, IIED and the Alliance for Responsible Mining have found that 63 per cent of mining operations are informal in the sense that they lack a legal title to operate.

In China, approximately 700,000 informal workers collect or recycle waste electronic and electrical equipment such as mobile phones, working outside formal employment regulation with little legal protection and often on low wages. As a large processor of domestic and imported e-waste, India is likely to have similarly large numbers, though these have never been properly counted.

In East and Southern Africa, up to 95 per cent of food is sold in informal markets. Six million consumers in Kenya drink milk from informal small-scale milk vendors — and in 2007 the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) reckoned these vendors supplied over 85 per cent of the market.

And it's not just food. A report (PDF) for GIZ, the German Federal Enterprise for International Cooperation, in 2010 estimated there are about 200,000 charcoal producers operating in Kenya, and that most of these are informal.

According to the International Labour Organization, the informal economy comprises half to three-quarters of all non-agricultural employment in developing countries, and the proportion is likely to be much higher if agriculture is included.

Many people in these informal trades and industries are female, so working with, rather than against, informality can help support women's and children's standing in society. For example, women's control over income correlates with improved food intake and nutrition for their children.

Governments and bigger businesses see formalisation and regulations as the route to greening and sustainability. But formalisation isn't always appropriate, and can risk both undermining functioning market systems and perpetuating illegality by driving markets underground.

Last week we held a workshop at IIED with participants from the ILRI, the Alternative Research Forum for Mindanao, Ghent University, Surrey University, Northwest Agriculture and Forest University, Kabarole Research and Resource Centre, and the Center for Agrifood Policy and Agribusiness Studies. The event explored how informal markets are governed, looking across multiple sectors and with case examples from the trades mentioned above, along with the banana trade in Uganda, street hawkers in Java, and the timber trade in Cameroon, and some striking commonalities emerged.

There is often a huge gulf between regulation and reality

Despite the evidence that informal markets play strong roles, national, regional, and local policymaking is often focused on, and biased towards, larger-scale and formal enterprise — which is more easily taxed and easier to monitor and measure. Donors also often ignore this gulf, and this often leads to governance approaches that work against the majority of producers and which damage their livelihoods.

In Kenya, for example, the government sought to ban charcoal production, which simply pushed production underground and increased opportunities for officials to extort bribes from producers.

Informal production is often no worse than its formal competitor

People often equate informality with illegality — thinking it's dirty and unsafe, bad for the environment, bad for consumer health, and bad for sustainable development. The evidence doesn't always bear this out. For example:

Efficiency: The informal waste sector tends to achieve higher collection rates than the formal, because people's livelihoods are at stake. Big institutions in China and India can successfully operate high-technology recycling plants, but often cannot access sufficient e-waste to be economically feasible. Informal collectors can help bridge this gap.

Safety and human health: Research into the milk sold through small-scale milk vendors and 'milk bars' in Kenya found that it had similar bacterial levels to those sold in formal markets.

Consumers prefer informality: Large numbers of Kenyan consumers prefer street markets to more modern markets: they are seen as affordable, accessible, and offering fresh food with trusted sellers and the option to access credit. Recycled electronic products produced by informal waste collectors and recyclers are far more affordable for low-income consumers than new products. And people disposing of e-waste prefer to sell it to informal collectors who will come to their doorstep and offer higher prices than formal collectors.

An important choice

All this is not to say that the informal economy is never inefficient, unwanted, dirty or dangerous — artisanal gold mining, for example, is responsible for a third of all mercury released into the environment.

But the informal economy is a reality and offers an important — and often the only — livelihood option for many of the world's poor.

Participants art the workshop agreed on the importance of looking for ways to reduce the damaging aspects of informal production and trade in a way that doesn't deprive the many people involved in the sector of their livelihoods. Treating people operating in informal markets as 'more human' (the Javanese concept of 'Nguwongke') has helped the government work with street vendors in the city of Surakarta in Central Java to successfully relocate them to cleaner, designated areas in the city, reducing conflicts associated with their sprawl throughout the city.

What we need now

Xiangping Jia, from China's Northwest Agricuture and Forest University, nicely summarised the workshop's consensus on what we need now:

- Better facts that document and acknowledge the reality of informal markets — their size and how they are currently governed, looking across sectors to gauge their impact on and contribution to the whole economy

- Better theories of economic and social development based on recognition of informal markets

- Better tools for achieving transformational change that goes beyond the small success cases, but that is built on their evidence of what works, so that that policy makers, investors, donors and others can support and work with informal markets

- Better actions for improved and inclusive governance of informal markets, including hybrid models that link people in informal markets with the formal, and

- More research and targeted engagement between researchers, practitioners and decision-makers (donors, government at all levels and big business) – IIED's workshop strove to set the foundations for a growing community of practice around informality.

Emma Blackmore (emma.blackmore@iied.org) is a researcher in IIED's Sustainable Markets group