Shining a light on energy consumers in rural Tanzania

Chih-Jung Lee examined what's driving energy use for villagers in Tanzania. In this blog, Lee shares her findings and offers insights to mini-grid developers for meeting diverse consumer demand.

The sun beats down on Dongo village, Tanzania. Children walk with cattle while women carry water buckets (Photo: Copyright Chih-Jung Lee)

Navigating an unexplored market isn't an easy task. And mini-grids developers providing electricity to rural consumers in sub-Saharan Africa understand this sentiment well.

These customers are among the hardest to reach. In rural Africa, 482 million do not have access to electricity, and most of these are in sub-Saharan Africa. The energy needs are huge, and the potential of this underserved market is immense.

Developers recognise this potential but often lack reliable information on consumer priorities and spending patterns. When it comes to understanding rural consumers' purchasing power and behaviour, mini-grids developers often find themselves in the dark.

Through my work with Rafiki Power, a mini-grid start-up owned by E.ON, I wanted to dive into the lives of rural customers to better understand their electricity consumption behaviour. As part of my research I visited eight villages in northern Tanzania.

I wanted to know how rural households' electricity consumption relates to their socio-economic situation. I had assumed that the more land a farmer owns the more livestock a herder keeps, and the more kids in the family – the more electricity that household will consume.

My findings showed very much the contrary. Even a large household with lots of kids and a herd of cattle on a good-sized plot of land consumes only modest amounts of electricity if income is limited.

So, what's growing farmers' energy use?

My research found out what's really driving consumption in farming households: new electrical appliances. A few months after the harvest season, when a family has received income from sales of crops, it's very common to spend a few thousand shillings on a new TV. This can drive up household electricity consumption by an average of 0.4 kWh per month. Or a well-off family – with average monthly consumption of 5.6kWh – might decide to buy a new freezer; this boosts consumption significantly – by about 3 kWh a month.

Local businesses: profits power energy demand

When I looked more closely at the consumers with largest electricity consumption, I found myself in the village centre, surrounded by bustling business activities such as salons, bars, guesthouses, leather processing and candle-making.

One in four villagers are business people and together consume more than half of the village's total electricity.

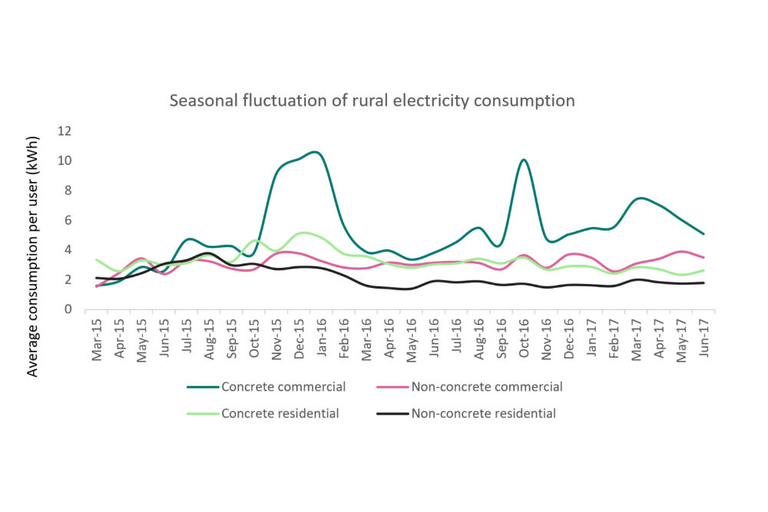

Businesses' electricity consumption level is less limited by their income level, but by profitability of their business – their use of electricity is an investment in business operations. The most well-off of these business owners, namely those trading in concrete houses at the centre of the village, consume three to four times that of regular households – as shown in the graph below.

After harvest, when people have more cash, bars and restaurants thrive and electricity consumption picks up. On the other hand, during Ramadhan, economies become much less vibrant, particularly in predominantly Muslim villages. Trade is less active, and energy consumption drops.

How mini-grid developers can meet diverse and fluctuating demand

The market for mini-grid developers is diverse and holds huge potential. Mini-grid developers can serve customers better by providing more customised services.

The following insights can help guide mini-grid developers:

- The most significant wealth indicator in rural villages is house type and ownership of non-farm business activities

- Short-term increases in household income (eg harvest) do not translate directly into higher household electricity consumption, but indirectly through commercial activities in the village

- Marketing household appliances to rural households, especially low-consuming households directly after the harvest season, could encourage electricity use. Financing to purchase these appliances is also key. Mini-grid developers would therefore benefit from finding marketing and financing partners to work with

- Businesses' electricity demand fluctuates more than for households and is more sensitive to price changes. Special tariff design can increase businesses' consumption levels. Providing a larger breaker (an electrical switch that protects the system when there is an overload) would allow businesses to use electricity with more flexibility, and

- Income is the main barrier for regular households to take up higher electricity consumption. Therefore, training to increase local productivity using electricity by introducing modern, industrial process and equipment paves the way for mini-grid developers' long-term growth.

Rural electricity consumers in developing countries cannot be treated as a homogeneous market and a one-size-fits-all approach will not work.

Consumers range from business owners with high demand to farmer households who need to build their understanding of how to use electricity more effectively. With findings from my research in northern Tanzania, I hope to support mini-grid operators in understanding this underserved market and unleash its growth potential.

Chih-Jung Lee (chih-jung.lee@rafikipower.com) is a business analyst with Rafiki Power. This article is an excerpt from her research on consumer behaviour. The Energy Change Lab, a programme of IIED and our partner Hivos, is running a prototyping programme that supports Rafiki Power and others to test out solutions that can help stimulate 'productive use' of energy in rural Tanzania.