Q&A: Achieving housing rights for all: issues and recommendations

How can we address the global housing crisis, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic? Housing experts answer questions from a recent webinar that discussed housing insufficiency around the world.

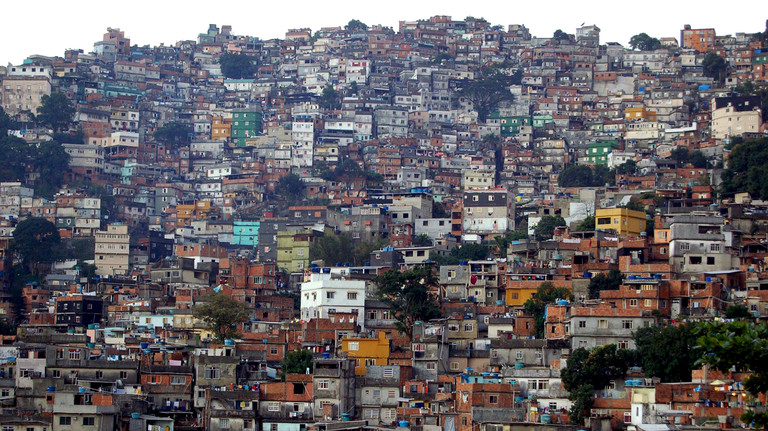

A favela in Rio de Janeiro, with densely populated homes. In Brazil, more than 100 million people lack sewage collection (Photo: metamorFoseAmBULAnte, via Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

Coinciding with World Habitat Day 2020, on 5 October 2020 IIED hosted an online discussion about the shortage of adequate, dignified housing during the coronavirus emergency.

Moderator Diana Mitlin, IIED principal researcher and professor at the University of Manchester, along with panellists Anna Muller, national coordinator of the Namibia Housing Action Group; Lajana Manandhar, executive director of the Lumanti Support Group for Shelter; and Higor Rafael de Souza Carvalho, an urban planner and PhD candidate at the University of São Paulo, debated the deficient housing situation across Namibia, Nepal and Brazil, the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, and their recommendations for change.

Here, the Environment and Urbanization team address four key questions raised by the webinar’s attendees:

Q: What are the gendered impacts of COVID-19 on housing? To what extent can social relations, such as gender relations, be an integral part of the COVID-19 response rather than an add-on?

It is clear that housing inadequacy affects different groups in a variety of ways. As ever, low-income, displaced and other marginalised populations have particularly limited choices, and gender is frequently a factor in housing access.

Mitlin pointed out that for many women in low-income countries, the home has long been a site of work, even before the pandemic. In Latin America, for instance, women’s disproportionate burden of domestic work – in-home paid work, household tasks, caring responsibilities and now COVID-19 management – are making the home a particular site of vulnerability.

Gender also intersects with many other social identities to shape experiences of housing. Among the female workers attracted to Hawassa, Ethiopia, by the employment prospects offered by a large industrial park, married women face fewer housing challenges than young, elderly, single, divorced and widowed women. In a very different context, caste-based housing discrimination is actually worsening in most Indian cities, particularly smaller cities.

So context is crucial for understanding how social identities influence shelter. For example, in Mogadishu, Somalia, people with disabilities and young single men are often blocked in their efforts to obtain shelter.

Carvalho highlighted the increase in violence against girls and women during the pandemic. In several Latin American countries, he reported, the numbers of feminicides during the lockdown increased by 20-30% when compared to the data from the previous year.

This shows that housing policies should consider and be equipped to deal with gender-based violence. Programmes should be designed to not only provide families with shelter, but to be able to identify cases where services are needed to support the abused.

Q: What are the links among densities, informal settlements and the COVID-19 pandemic?

While during early stages of the pandemic, infection statistics led some people to demonise urban density, a more nuanced analysis suggests that it is inequality, not density, that makes certain urban residents particularly vulnerable to viral transmission.

Although social distancing is more challenging in dense areas, wealthy urban residents are less exposed to the risks of overcrowded housing and poor living conditions. They can enjoy the social, economic and environmental amenities of city life with fewer vulnerabilities.

As Carvalho added, Hong Kong, which is one of the world’s most densely populated cities, has not had a large number of COVID-19 cases – unlike in Brazilian informal settlements, which are also high-density areas.

One silver lining of this devastating health crisis is the social awareness decision makers are acquiring in terms of the link between housing and health. The acknowledgment that housing is inextricable from public health has to move beyond physical structures, to involve basic services and healthcare as well.

For instance, insufficient water supply and sanitation makes it challenging to observe recommended hygiene measures. In Brazil alone, more than 100 million people lack sewage collection.

Organised local communities have taken steps to address inadequate housing conditions during the pandemic. In Buenos Aires, for example, community priests have allowed elderly residents of overcrowded homes to shelter in chapels.

However, longer-term measures will be needed to ensure improved housing conditions, increased affordable shelter and basic service provision, particularly in the informal settlements that are so often neglected by governments.

Q: To what extent are housing rights and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) changing government approaches?

The SDGs and the New Urban Agenda, signed in Quito, Ecuador in 2016, are important diplomatic commitments towards housing and urban rights. In many cases, these inspired national and local governments in the creation of cities’ planning documents and new housing policies.

However, these diplomatic pledges are also subject to context-specific political disputes at the local, national and international levels. As urban planner Carvalho described, in many Latin American and Caribbean countries, the right to adequate housing is embedded in national constitutions. But governments often fail to guarantee this right to all.

In Carvalho’s view, it is still too early to identify whether these agendas have resulted in the effective transformation of government approaches.

Q: How has COVID-19 influenced recommendations about the housing crisis in the global South?

Poor quality housing has always been an urgent issue, but the pandemic has given it special visibility.

One of the most pressing needs is to stop evictions. Even during the pandemic, evictions have continued in Namibia, Nepal and many other countries – making ‘shelter in place’ orders impossible to follow for many people.

It is also important to nurture good governance. Robust democratic institutions should be accountable for housing policies that look great on paper, but are never implemented for the urban poor.

More positively, we have seen overlaps in addressing housing insecurity and COVID-19. The combined shelter and health crises have drawn attention to the need to listen and support urban poor organisations, as they already have the knowledge and experience of improving housing locally.

Central governments cannot possibly know the intricacies of an informal settlement as well as the residents themselves. As Muller stressed: “To have organised communities to respond to the crisis is very important.” For example, citizens’ groups have helped to curb evictions in some self-built settlements of Istanbul through a combination of legal and political strategies.

Panellist Lajana Manandhar did not mince words when calling for imminent change: “We have to do something now. We have to take radical steps.”

- To receive updates on IIED’s urban events and publications, sign up to the urban newsletter

- The October 2020 issue of Environment and Urbanization on 'Rethinking the roles of the state and communities in urban housing and land-use management' is now available. Email eandu@iied.org if you require access to any of the papers, or subscribe to the journal.