IIED builds a fairer and more sustainable world by amplifying marginalised voices, challenging unsustainable policy and practice with evidence and analysis, and promoting debate on key challenges for our common future.

We develop practical, innovative propositions for sustainable policy and practice, working with stakeholders to refine and apply them. In 2017/18, our independent research approach – with meaningful multi-stakeholder dialogue at its heart – proved more relevant than ever.

Disruption from political, social and technological change continually creates challenges and opportunities. We saw the strength of our participatory methods reflected in our achievements – work with IUCN to ensure community voices are heard in conservation initiatives is influencing policy in Southern, Central and Eastern Africa; a project with the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights is empowering female community representatives to influence the debate on urbanisation and food insecurity.

But the challenges remain significant. Inequality is increasing in many dimensions and progress in tackling the global climate crisis is distressingly slow.

In 2017, IIED welcomed an independent external review. It noted our approach to policy dialogues as ‘highly relevant in the coming 10-15 years, in particular with regards to realising the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)’. The review identified three further ‘impact pathways’ through which we deliver real change: research to policy; targeting policymakers; and by empowering the marginalised.

These pathways help define what makes IIED unique in the development and environment space. They frame the inspiring stories you will read below.

But the quality of an institution isn’t just measured by what we achieve; how an organisation works is as important as what it does. So we have further increased our efficiency: improving financial and other systems, embedding gender in every aspect of our work, and enriching our monitoring and evaluation.

We will continue to bring together diverse interests in the name of social and environmental justice. For now, I am proud to present a snapshot of IIED’s work in 2017/18.

Andrew Norton

Multi-stakeholder dialogues

Our multi-stakeholder dialogues connect marginalised people with key decision makers, including government, development practitioners, academics and technicians. IIED's expert facilitation delivers co-created and locally rooted evidence, which in turn inspires policy and practice driven by social and environmental justice.

Digging deep for solutions in Tanzania

Artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) of some of the world’s most valuable metals, minerals and gems can create sustainable jobs for millions of marginalised men and women and build strong local economies in the world’s poorest countries.

But exploitation, poisoned landscapes and violent conflict have given ASM a bad name. For governments of resource-rich countries, it is often the toxic sector that’s easier to ignore.

This year, IIED advanced its pioneering action dialogue programme in Ghana, Madagascar and most recently in Tanzania, bringing together key players to address the sector’s most contentious issues and generating evidence to change outdated policies and attitudes.

It’s a sensitive and highly political process: governments distance themselves from ASM’s social and environmental problems, while miners mistrust the politicians who repeatedly fail to recognise their rights and needs. Tensions persist as large-scale international operators and ASM communities compete for valuable territory.

Small-scale and artisanal miners working in challenging conditions, Tanzania. Photo by Brian Sokol/Panos Pictures

In this landscape, our dialogues create a neutral space for local and national government, large-scale mining companies, mineral processors, investors, mining organisations, and women and men miners to identify challenges and create a solutions-focused roadmap for action. Rarely do such diverse actors with such broad agendas meet.

We recognise that powerful stories inspire change. The dialogue process invited unheard voices – miners, suppliers and traders – to share their successes, struggles and where they see the sector’s greatest opportunities. Stories of optimism and determination from an entrepreneurial, self-organising ASM community – especially women – brought rich experience and hands-on knowledge of what’s needed to create sustainable, profitable livelihoods: from access to markets where miners can sell their goods to technologies that make their practices more responsible.

Crushing the rock with hands and hammers is very hard. If we get the good machines and good technologies, we can be big and get to the national level and even international.

– Mwanahamisi Mzalendo, ASM miner, Tanzania

In Tanzania, one of our biggest wins of 2017/18 was securing consensus to set up government-led ‘excellence centres’ right next to the mines where ASM workers operate.

These centres will be one-stop hubs providing services such as business and finance training, geological data and mineral processing facilities. The centres will also connect miners with city traders who deal with high-end international buyers – enabling them to sell their goods within proximity to the mine while getting the biggest bang for their buck.

Other agreed solutions include new regulations that support miners’ access to higher quality, mineral-rich land and user-friendly government-led online systems that provide practical advice such as how to apply for mining licences.

Our co-created evidence is well-timed – coinciding with the Tanzanian government’s drive to reform mining policy. Now we are working with influential bodies including the ministry of minerals, land and local government, the Tanzania Chamber of Minerals and Tanzania Women Miners Association to package it up, ready to put to decision makers at the highest level.

Targeting policymakers

We identify strategic opportunities for policy intervention at local, national and global levels. IIED has an impressive track record of working with decision makers to further develop their capacities in creating and using evidence, and help them to recognise the realities of the poorest people and reflect these in policy.

Ramping up LDC support as 2018 deadline closes in

The landmark Paris Agreement on climate change committed signatories to reduce carbon emissions and pushes for a 1.5 degrees Celsius cap. Now nations are negotiating the ‘rule set’ that will govern the commitments and financial pledges made in Paris. Securing ambitious rules is a major focus for IIED ahead of the deadline at the end of 2018.

Those with most at stake are the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) – the world’s poorest nations who are least able to cope with increased risk of floods, droughts, hunger and disease.

The workshop helped me focus on LDC priorities: we must stick together - as a team our voice will be louder.

– Ms Xaysomphone Souvannavong, climate negotiator, Lao People's Democratic Republic

The LDCs have led from the front in the global push for climate action and were instrumental in shaping the Paris Agreement. But they remain vulnerable, they need the UN climate talks to secure tangible commitments. If their climate negotiators are too few in number, are inexperienced, or have not agreed a collective position on which policies to push for with a clear strategy for how to get them, the outcome of the talks will be weak: high aspirations and good intentions that lack concrete action.

This year, IIED – as part of the European Capacity Building Initiative (ECBI) – trained and supported LDC officials to increase their influence in the crucial rule set negotiations. Over 100 delegates from more than 40 countries built their skills in navigating the notoriously complex climate negotiation process. They were also armed with practical knowledge on how to implement the outcomes back home, in their national climate action plans.

Pa Ousman Jarju, former chair of the LDC Group in the UNFCCC negotiations, confers with IIED's Achala C Abeysinghe at COP21, Paris. Photo by Matt Wright/IIED

Our team of experts were joined at the training by experienced climate negotiators who have already benefited from our support, including the current chair of the LDC Group. Together, we briefed delegates on specialist issues, how to unpick technical jargon and interpret legal text, and gave guidance on making strategic interventions. Our ‘mock negotiations’ allowed participants to practice their new skills in realistic simulations.

With ECBI, we paid attention to improving the LDC delegation’s gender balance, helping ensure women’s perspectives are heard. Over 40% of our workshop participants were women, including four from Afghanistan, Angola, Comoros and Laos who attended the negotiations through our direct support.

The value of supporting the LDCs cannot be underestimated; during the Bonn November talks, the delegation voiced its strong support that the Adaptation Fund – which has provided developing countries with direct access to climate finance – be formally recognised as one of the funding streams to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement. This was successfully negotiated – a major coup for the LDCs. In the coming year, we will continue to amplify these countries’ voices in these crucial talks.

Research to policy

Working with local actors and partner organisations in the global South, we develop practical solutions that support pro-poor governance. Together, we present policymakers with a rigorously researched evidence base for fairer ways forward, from local level to global scale.

Lions, livelihoods and the power of listening

Safeguarding Africa’s iconic animals from the illegal wildlife trade (IWT) is vital. But what happens when wildlife destroys crops, hurts or kills people, and yet is more protected than local communities? Conflict between humans and animals harms both, while a response focused on law enforcement often fails to protect either.

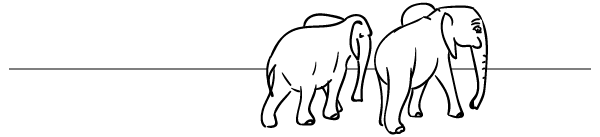

Through extensive community consultation in Kenya in 2016, IUCN and IIED’s ‘First Line of Defence’ initiative tested an innovative theory of change. It engages communities in tackling IWT by: reducing the costs of living near big cats, elephants and other wildlife; growing incentives for conservation; increasing disincentives for poaching and other illegal activity; and supporting sustainable alternative livelihoods.

If a rhino is killed, the government comes immediately to find out what happened. If a person is killed or injured, nobody comes.

– Community representative, Kenya

Putting theory into practice involves connecting those designing conservation projects with the local people that their programmes target – people whose insights give plans to halt IWT a far higher chance of success.

In 2017/18 the initiative delivered real results. Testing our theory of change near the Masai Mara National Reserve and Amboseli National Park highlighted how different community, private sector and NGO perspectives on conservation programmes can be – and how they can be brought together. Listening without judging and reporting without prejudice are critical to this success. Now tools and guidance based on our experiences are enabling replication of this dialogue-based approach.

Participative exercise to discover community perspectives on conservation projects, Olderkesi Conservancy in the Masai Mara, Kenya. Photo by Micah Conway

Others are keen to adopt our methodology: USAID’s strategy for extensive IWT work across Southern Africa includes the First line of Defence approach; a report by wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC also recommends our thinking to inform conservation programme design in Central Africa. The outcome: communities are included and empowered, not ignored and punished.

Related work with the University of Oxford and Wildlife Conservation Society-Uganda also secured policy change. Our 2016 research into what fuels wildlife crime in Uganda’s two largest conservation zones – Murchison Falls and Queen Elizabeth National Park – identified poverty, human-wildlife conflict and lack of alternative income. In 2017, we created sustainable, pro-poor action plans: community-based approaches for tackling IWT endorsed by the Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA).

This year, thanks to UK government funding, we are making the Murchison Falls plan a reality. Working with UWA, we are supporting a pilot project to recruit local people as wildlife scouts, helping reduce human-wildlife conflict and increase wildlife crime reporting. With development specialists Village Enterprise, we are establishing new income opportunities for the households of the volunteer scouts.

In March 2018 we coached 23 UWA community conservation wardens on improving local engagement, conflict resolution and gender awareness. Their enthusiasm bodes well for a more effective and inclusive approach to tackling IWT.

Our work in Uganda continues. Sustainable IWT interventions must involve all interested parties, from community representatives to international NGOs and oil giants. We are sharing our considerable experience of convening diverse groups through the Uganda Poverty and Conservation Learning Group, and will be working with the Uganda Conservation Forum to create a dialogue space for all voices.

Empowering the marginalised

We help poor and excluded people and nations to create and use evidence to ensure they are heard and hold their own in decision-making arenas that affect them — from village councils to international conventions. Sustainable development is about people, as well as places.

Grassroots research delivers fresh take on food insecurity

IIED's urban research – built on strong relationships with southern organisations and a belief in giving voice to marginalised communities – delivers valuable, hard-to-reach evidence. In 2017/18, we used our signature approach to ask urban citizens living in poverty a crucial question: how do you define food insecurity?

We know future population growth will be concentrated in urban Africa and Asia. We know poverty and other challenges to food security in towns and cities will punish the most vulnerable people. Yet authorities typically lack the data to plan a food-secure future; most related policies linger on production but overlook access, affordability and other vital consumption factors that hinder access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food.

An urban street vendor provides an affordable, accessible food option, Cambodia. Photo by Chiara Abbate/Flickr via Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

For effective solutions, we must first achieve a genuine understanding of the problem. The real experts – poor urban communities – must urgently be heard in the food and urbanisation debate. In 2017/18, we partnered with the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights (ACHR) to realise this.

An initial project design workshop, facilitated by ACHR and IIED in Thailand, set the bottom-up tone in December 2017. ACHR – a network of community organisations, NGOs and professionals working on urban poor development – brought together community leaders from Nepal, Cambodia and the host nation. Rich learning and sharing both epitomised project values and shaped its design.

Early 2018 saw the first project phase launch. We supported ACHR to host meetings in Kathmandu and Phnom Penh, asking leaders of organised urban community groups to define their experiences of food insecurity. These women know all about feeding their families with little money, security and time, often in settlements beleaguered by environmental hazards.

Food security is a very big issue, it affects everybody all the time, more than eviction. Many people die young and unhealthy because of food.

– Somsook Boonyabancha, chairperson, ACHR

Amplifying community voices is not only right, it works. Just a year in, we are shifting thinking on food and urbanisation. The project's transformational focus on urban consumption engaged academics in a strategically related field: our peer-reviewed article in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health was viewed or downloaded almost 1,500 times in six months by people from all over the world. Additionally, our inclusive research approach secured funding from the rigorous and prestigious Economic and Social Research Council, winning out in a highly competitive process.

In 2018, we will continue our partnership with ACHR, exploring how disenfranchised urban communities in Cambodia and Nepal's smaller towns characterise food insecurity. We will also investigate how urban planning and street food affect consumption, and explore urban communities' own solutions to food insecurity, through initiatives like community vegetable gardens and communal kitchens.

Finally, we will bring grassroots groups and other participants together to share learning at city, national and regional level, before taking their evidence to policymakers.

IIED annual report 2017/18

Our annual report looks at how IIED’s ways of working help us to deliver lasting impact in a shifting global landscape.

Download the full annual report from our Publications Library