China’s investments, Africa’s forests: from raw deals to mutual gains?

The grand-scale Belt and Road Initiative is driving ever greater Chinese investment in Africa’s forests. But will the benefits of this ‘development’ reach local people? And will it be sustainable? A recent IIED project in Cameroon highlights both the potential and the pitfalls of surging investment.

Logged trees for export to China at a Chinese timber company, Beira Corridor, Mozambique (Photo: Joerg Boethling/Alamy Stock Photo)

China is pursuing the biggest global development project ever. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) easily beats the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement in terms of money on the table.

In just six years, BRI co-operation agreements have been signed with 126 countries and 29 international organisations. Its investment is predicated to rise to over US$1 trillion over the next decade. There is no doubt that BRI is a global game changer; it is the nature of that change which remains a question.

IIED’s priorities include bolder action on the climate emergency and prioritising nature in development; public opinion is now surging the same way. This would be a good moment for BRI to confirm that its huge infrastructure surge – sometimes linked to deals in which China secures natural resources – will morph into the world’s biggest sustainable development project.

Green intentions, or sustainability actions?

Beijing’s recent Belt and Road Forum heard much new and encouraging talk about mutual benefit, inclusive approaches and green and sustainable development. But action on the ground is what counts.

Building infrastructure creates huge emissions and sucks up overseas resources, while conveniently venting the excess capacity of a slowing domestic economy. While accusations of predatory lending and creation of debt traps appear to be politically motivated and overblown, building new coal mines and power stations in African nations and elsewhere do little for BRI’s green credentials.

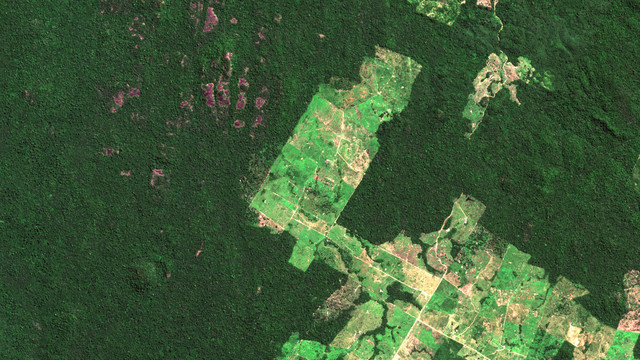

Some consider BRI the most environmentally risky venture ever. Others are exploring its links to deforestation.

Africa has leverage too

Yet, just because China gains geopolitical and commercial influence from investment, it does not mean that host countries can’t benefit too.

African leaders citing ‘freedom from conditionalities’ as a key attraction of China-backed investments is understandably met with scepticism by those concerned with environment and development. But clearly BRI investments could be of great benefit in Africa if they are the right investments, designed in the right way, and carefully negotiated at local level.

African states are not just passive recipients of China’s masterplan. However, decisions by African leaders on China-backed projects seem largely pragmatic and short term, with little citizen engagement. Even before investments get under way, speculative land deals can create a new political economy around prospective sites – and there are losers as well as winners in this ‘economy of expectations’.

A spectrum of investments

Large Chinese companies were already increasingly influencing the pace and scale at which Africa’s trees and forests make way for agro-industries, mining and infrastructure development before BRI. But BRI gives these companies a new boost.

In addition to this, an overwhelming majority of ‘Chinese companies’ in Africa are small and micro businesses that are locally incorporated rather than the tentacles of state interests. Much Chinese investment takes the form of small-scale private ventures: restaurants, shops, small farms and the like. These businesses are often registered by Chinese migrants using savings they have earned locally, as employees of the bigger investments.

Cameroon: development theory in reality

New research, conducted by IIED and local partners the Centre for Environment and Development (CED), looked at how Chinese companies are affecting Cameroon’s forests and the people who rely on them. We found a fast-changing picture in which Chinese investments are now worth twice as much as all of Cameroon’s other sources of investment combined.

Two major rubber plantation and processing developments have been taken over by the same parent company and, while some local jobs and corporate responsibility initiatives have improved, there is a growing web of interconnected problems: high-level political manipulation; questionable land titles; large-scale displacement of local communities and indigenous people; high biodiversity-value forest loss; illicit timber trading; and rising environmental costs.

Kribi is home to one of China’s biggest global port investment projects, as well as a variety of other infrastructure initiatives including the Memve'ele hydroelectric dam, the Yaoundé-Douala motorway and drinking water supply in four major cities. These projects generate a range of problems for forests and people, including forest loss and social conflict. The latter stems in part from minimal interaction between Chinese and Cameroonian workers, or between companies and citizens.

China is also now Cameroon’s biggest timber buyer. But, like those from other countries, China-linked forestry companies, small forestry enterprises and traders need to improve their compliance with the law, improve the sustainability of their operations and increase local product processing.

Currently, communities tend to get little return from forest exploitation, while the forest itself continues to be badly degraded in many areas and sometimes illegally converted. Indigenous communities are particularly hard hit.

Pushing back for real, protected benefits

Working with CED, the Global Environmental Institute (a Beijing-based NGO) and key players in the Cameroonian government, IIED was able to make some progress in securing commitments from Chinese businesses to respect local tenure and laws and to increase engagement with and the capacity of local communities.

Our work shows that forums for community engagement – which the large infrastructure companies are beginning to set up and sustain with local government and communities – have real potential.

It also demonstrates the possibilities of working with associations of Chinese small enterprises that individually remain off the radar to date. A a group of Chinese enterprises that together account for much of the timber heading to China were stimulated by our work to register an association committed to legal practice and ready to engage with government.

Maximising potential, avoiding pitfalls

In exploring these possible China-Africa forest partnerships elsewhere, we have found Chinese companies that show real potential to be innovators in sustainable land use. We are building on experience, thanks to our work in the Democratic Republic of Congo supporting organisations of artisanal loggers to make better deals with Chinese companies, in Uganda on NGO-government-company dialogue, and in Mozambique on new Chinese investments in industrial parks founded on the basis of benefits to local livelihoods and sustainable use of forest resources.

The true intent of these companies – large and small – will be revealed in time. Until then, NGOs and governments must keep taking action to improve evidence, dialogue and capacity, as well as contribute to structural reforms that enable more widespread development of locally beneficial sustainable land use.

It is equally important that Chinese markets are pushed and pulled towards commitments to sustainability and that the due diligence and responsibility of Chinese companies abroad are tracked and scrutinised in China. Initiatives geared towards shaping a leading role for China in a new global 10-year framework to tackle the alarming rate of biodiversity loss should help here – it is due to be signed in Kunming in October 2020.

If locally-negotiated deals and responsible investments are reached, Chinese businesses – the key driver of land use change in Africa – could also bring major innovations for sustainable development. Then, perhaps, the BRI will indeed outstrip all others as the sustainable development initiative of our time.

About the author