Is adaptation the missing ingredient from the new UN biodiversity action plan?

This week governments from across the world will meet in Rome to discuss the first draft of a new global action plan to tackle biodiversity loss. Dilys Roe asks whether there is something missing from the agenda.

Combine harvesters in a wheat field in India’s Punjab region. Just four crops – rice, wheat, maize and potatoes – provide more than 60% of the world’s food (Photo: Borlaug Institute for South Asia, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

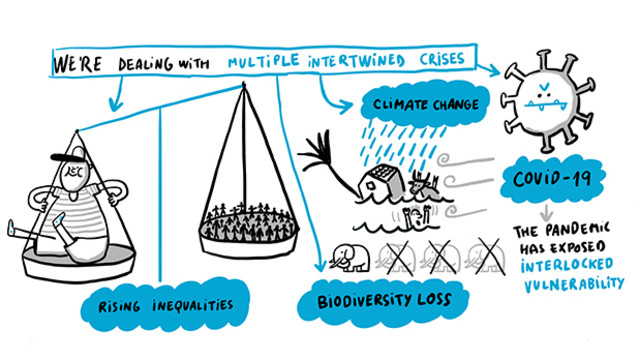

Last May, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) released a landmark report on the state of global biodiversity. Written by 145 authors from 50 countries, the report documented unprecedented rates of decline in natural ecosystems and species populations.

Since then, experts have been debating how much land or sea can be protected; how much degraded land can be restored; how many ecosystems can be retained; how many species can be saved from extinction. The focus of discussions to date has been on reducing the rate of biodiversity loss – and ultimately halting it.

What has not been discussed is whether we should also plan for adaptation to biodiversity loss.

Learning from climate change debates

In the language of climate change, taking action to halt or reduce the rate of biodiversity loss is mitigation. Mitigation is the primary focus of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Climate change adaptation, on the other hand, is about responding to the effects of climate change – both positive and negative.

Within climate change diplomacy, adaptation was considered almost a taboo subject for many years because it was considered that it would divert attention away from the priority of mitigation. In 2002, however, developing countries called for greater attention to adaptation on the basis that damaging climate events would occur regardless of efforts to mitigate emissions.

Has that same turning point arrived in biodiversity diplomacy? And if not, should it?

Could we adapt?

Using the same definition as for climate change, human adaptation to biodiversity loss would imply adjusting to low(er) biodiversity environments, and to the effects of that reduction in biodiversity. Some of those effects include (but are not limited to):

- Reductions in the immediate availability of food, medicine, fuel, fibre to the estimated nearly three billion people who depend directly on traditional agriculture, small-scale fisheries, wild foods and medicines for basic livelihood support. Some groups of people are heavily dependent on only a few species, meaning that even small changes in local biodiversity can present major threats to their livelihoods

- Reduced primary productivity and hence reduced crop yields, fodder production, fisheries production, leading to reduced food security

- Less diverse diets, leading to reduced nutritional security

- Reduced availability of keystone species and key functional guilds such as pollinators or seed dispersers

- Increased disease burden and reduced options for future drug development

- Reduced protection against pollution

- Reduced carbon storage and sequestration and hence reduced climate change mitigation, and

- Reduced resilience to environmental change and natural disasters.

The reality, of course, is that we have already adapted to biodiversity loss and continue to do so. Humans have always impacted ecosystems and biodiversity in their efforts to build livelihoods and speed economic development.

In the majority of cases this has resulted in large-scale decreases in biodiversity, and an increased homogenisation of those components of biodiversity that are most useful to humankind.

Take the food sector: out of the thousands of species that have been cultivated or collected for food, just four crops – rice, wheat, maize and potatoes – provide more than 60% of global human food requirements. But this lack of diversity in our diets seems perfectly normal to the majority of the world’s population.

And it's not just a lack of diversity in the food we eat. The way we produce food has also adapted to biodiversity loss, with chemical fertilisers and pesticides replacing the role of soil biodiversity and natural predators. More experimental approaches include the use of drones in response to declines in pollinators.

Beyond food production, we can see adaptation in the form of engineered flood defences that have replaced depleted mangroves and manufactured drugs that have replaced traditional medicines.

Looking ahead, a recent report by the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) highlights the potential of synthetic biology (PDF) to help us adapt. In one area of research, so-called ‘resurrection biologists’ are exploring the potential of ‘de-extinction’ – using ancient DNA to recreate extinct species.

But just as climate change adaptation was initially dismissed as a distraction from the priority of mitigation, so de-extinction has been described as ‘a fascinating but dumb idea’ that would distract (and take resources away from) the priority of saving endangered species and their habitats.

Should we adapt?

Adaptation to biodiversity loss – or to some effects of biodiversity loss – is clearly possible. The challenge perhaps, is not so much whether, or how, we can adapt to biodiversity loss, but how adaptation approaches can be available and affordable to those hardest hit by biodiversity loss – the world’s poor.

These are the people and the countries who are most dependent on biodiversity and least able to afford substitutes for its loss, or the technology to develop replacements.

Unlike climate change, where many of the effects are irreversible, nature degradation can be reversed and biodiversity can be restored. But reduced biodiversity environments are still a reality for many people in many places both now and in the future.

At least starting to talk about adaptation would increase discussion about the sustainability and equitability of current approaches, and stimulate greater attention to innovative, pro-poor solutions that help both people and nature respond to biodiversity loss.

Climate change adaptation is now mainstream, not only in international climate diplomacy but also in national and local level planning. As negotiations start on the post-2020 plan for biodiversity, will adaptation to biodiversity loss also become mainstream?

This blog is based on an essay (PDF) written for the Luc Hoffmann Institute’s Biodiversity Revisited initiative