Saving trees or improving lives?

Tackling illegal logging in Zambia's forests

"Cutting brought many good things for me and my family," says Andrew, pointing to the brick house behind him, a rarity in this remote village. Andrew is one of thousands of Zambian villagers whose lives have changed for the better because of the recent surge in mukula trade.

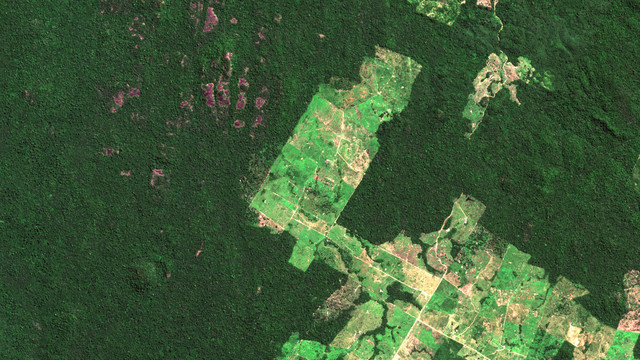

Coveted as a material for traditional luxury furniture in China, the mukula (Pterocarpus tinctorius, also previously known as P. chrysothrix) is a rosewood-like tree abundant in Zambia. Forests in Zambia cover 60 per cent of the country, roughly 45 million hectares, and close to 10 million Zambians live in rural villages near the forests – farming, collecting firewood and doing small trades. For many, the mukula trade has improved their livelihoods.

Andrew squats outside his brick home with his family and talks about how he sold mukula trees to buyers from outside the village.

I could afford a brick home for my family because of mukula.

Trees disappearing fast

Benefits to rural villagers have come at a cost to the forests, however. "The rush started around 2012. The Chinese buyers were looking for mukula trees everywhere in the country," says Ms. Mercy Kandulu Mupeta, from the Forestry Department of Zambia. Previously of little commercial value, the timber suddenly became a major source of income in the country, especially among rural villagers. This led to a nationwide scramble for the resource.

logger talks about the dwindling resourceWe started going deeper and deeper into the forests. Nowadays, we walk for several days to find a good tree to cut. It wasn't like this before.

The good trees are disappearing fast. Just like the threatened rosewood species in West Africa, if the cutting and trading continues at this speed, the mukula trees may be gone in the near future.

In response to the crisis, the Forest Department of Zambia has issued several measures aimed at controlling the trade, including a recent ban on movement of timber in early 2017. IIED, together with the Center for International Forestry Research, is currently working with the Zambian government to understand the economic, social and environmental implications of these policies.

Stockpiles of mukula in a log yard in Lusaka

Finding the middle ground: trees and people

Recent research shows that most efforts to control illegal logging, in Zambia and worldwide, focus on the strict enforcement of laws without fully considering the socio-economic impacts on the poor. Smallholders are disproportionately affected, with rural families often losing an important source of income.

What's worse, in some cases environmental damage continues unabated in spite of the government's targeting of illegal loggers. Big businesses are often allowed to keep exploiting the resource with minimal oversight from the government that suffers from lack of means and capacity. The result: forest degradation continues and large businesses thrive – while smallholders and chainsaw millers are pushed out of the timber trade.

a logger complains bitterly. The picture shows a mukula log with a price tag of $2 marked by a buyer in a log yard. The cut tree is estimated to be about 90 years old."Trees now sell for 20 kwacha, as little as a loaf of bread! This same size used to earn me 10 times more money before the regulation. But I need the cash to feed my family.

In Zambia, while our research is ongoing, we have observed the exclusion of small-scale loggers as one of the initial impacts of the exceptional attention paid by regulators to the mukula trade. While the environmental benefits of the regulations are not yet clear, the livelihoods of rural loggers have changed for the worse.

In some areas, they now make only a tenth of what they used to earn due to stricter government rules and sanctions. They have lost many buyers because the buyers are afraid to work with villagers directly under the stricter law enforcement. Even among villagers who still continue to log, many complain about getting a smaller share of the pie for the same hard labour because now they have to sell to a limited number of intermediaries and big businesses who control the market.

They are now criminalised as illegal loggers. But lacking alternative ways to earn money means that many loggers continue cutting mukula even without the proper licenses. The vast majority of them do not have criminal intent, they simply want to profit from an ongoing trade to support their families and pay for basic needs, such as school fees for their children.

Road ahead

The current set of regulations in place, with its focus on solving the environmental crisis, is jeopardising the livelihoods of rural loggers.

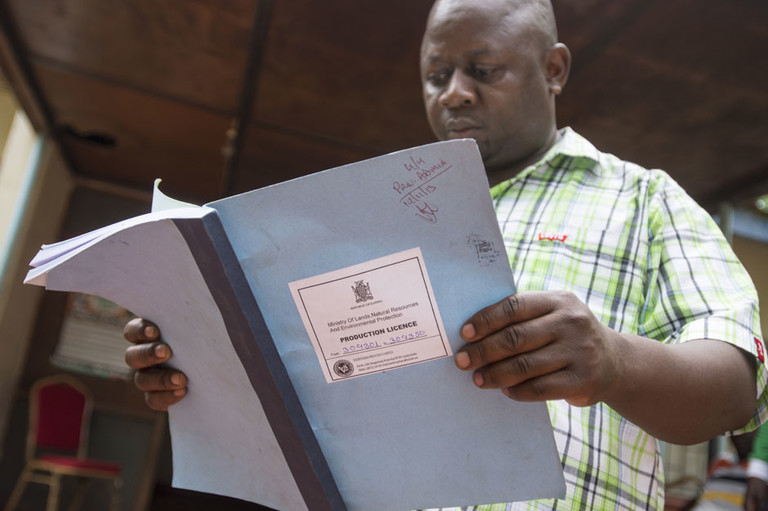

Mr Levy Nyangulu, a district forest officer from the Forestry Department of Zambia, checks the mukula production license issuance book

The good news is that the Zambian government has already taken steps in the right direction. The new Forest Code of Zambia, for example, allows for community forestry that gives rural communities a legal and legitimate way to earn money for valuable timber like mukula. Other options are also possible, and we're working closely with the government of Zambia to identify policy solutions that help both the environment and the people who live close to the forests.

Beyond Zambia, the mukula case offers another example of the need for illegal logging debates and regulations to recognise the trade-offs between rural livelihoods and environmental impacts. Smallholders and farmers-turned-loggers must have a seat at the policy table before any decisions are taken, rather than after. Otherwise, they will remain as criminals in their own forests because of policies made without their participation.

By Xue Weng, Paolo Cerutti, Penias Banda and Davison Gumbo; photos by Simon Lim and Paolo Cerutti

Further resources

- The chicken or the egg? CIFOR Forest news blog (March 2017)

- The rural informal economy: understanding drivers and livelihood impacts in agriculture, timber and mining Xiaoxue Weng (2015) IIED working paper

- Recognising informality in the China-Africa natural resource trade Xiaoxue Weng (2015) IIED backgrounder

The research mentioned in this photo story is being conducted in collaboration with the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), as part of the DFID-ESRC Growth Research Programme.